A Pillar of Salt and the Great Grey Wolf

This is the sixth entry from The Good Thief Dilemma: A memoir, a meditation, an investigation into the mysteries of spiritual abuse.

This is not my whole story.

It is not the story of my mother, or her lifelong dependency and the fictional world she created for herself.

It is not the story of my biological father and his hatred of his own body, the surgical wars he engaged in, the scarring and damage he had inflicted up and down his spinal cord to escape a phantom pain, a torturous pain that would not relent no matter how he cut or anesthetized himself.

I know those prologues and their epilogues. These are the stories of my bloodline, I know them. I own them. They belong to me. I won’t deny that were burdensome, but they were my inheritance, and they were mine to take possession of and make meaning from.

This is a story that no one ever told me.

This is a made-up story about real people and real events - and one real man in particular- who all made up their own lives and left me with so many secrets and distortions that any truth I construct is an accidental one.

This is a story filled with conjecture, confabulation, wild guesses, and stabs in the dark. It is about a stroke of lightening, a hurricane, about an apocalypse.

And it’s about the treasure that destruction sometimes leaves in his wake. This is the kind of story that we create when we try to make sense of egregious abuses, when we are harmed by cold hard evil.

Many people carry such stories inside of them. I’m not the only one.

I’ve made it my work, for over twenty-five years as a psychotherapist, to help usher these stories into the world, to hold space for words to come and rescue these stories from the depths of my client’s psyches.

Some people are destroyed, or harm others, with dangerous untold stories like these. Stories of failed empathy, of dehumanization and objectification, dark glimpses into the evils that can live inside a human heart - these tales send out rings of traumata, blast-rings of scorched earth flattening the horizon line.

There is often little evidence left behind in the devastation to bind these stories to the earth. Without words and without proof, such chilling tales can only be told through in fragments, in circles in time-loops, through incomplete flashes, by evocation, in dream-time, metaphorical re-visiting of the very dangers that were only barely survived, as we attempt to extricate the parts of ourselves that were annihilated, dehydrated, transformed into a pillar of salt.

This is the story of one decade, from age seven to seventeen give or take, and of a whole lifetime. And of a man, who I know almost nothing about, and who I know intimately. Who was not my blood but who was my Father, my priest, a de facto parent, and for a brief time my stepfather, a man who insinuated himself into my home, seduced my parents, destroyed my family, and stole our worldly goods. A teacher who both taught and terrorized me. A dark magician who I have been locked in battle with for fifty years - never mind that he has been dead for most of them.

I’d told the story out loud, in pieces, parts, and fragments - using as many words as I could recollect from the few that I had been given. I told through – but entirely out of sequence once, in my young adulthood, to a psychotherapist. I knew, in some way that I couldn’t pinpoint, that a wordless story was steering me into a secondary set of repetitive dangers. I found every word for it that I could.

I began seeing the twenty-five-year-old therapist when I was twenty-one, twice a week. I began noticing that I had symptoms, which I had never noticed as symptoms before. I would spend hours getting dressed, unable to see myself accurately in the mirror not because I was fussy about clothes but because I unable to tell what I looked like. I was not a night owl, I had regular, severe insomnia, terrible nightmares, intrusive memories, flashbacks, night-shame from my increasingly obviously not-so-normal childhood.

I tried to tell the kind young therapist the story so far - to recount, recall and reorder for myself what exactly had happened. I came into each session and told some other part of the story. I told him - and myself - for the first time what it actually felt like, parts of the story that I had ignored, the distressing, disturbing, terrifying, traumatic memories that swirled in my head instead of sleep. There was no familial or social relationship that would have listened. And my own shame and dissociation made it impossible to tell even if there had been.

At the end of seven years, which is almost as long as it took to live through it, I said: "I think I am finished telling you what happened." And I noticed that he was still in the room. And that he hadn't left, or become terrified himself, or ever once looked away. That he had stayed through all of it. That I finally had a witness, who had heard the whole story, who had traveled from my first home, and then after my family exploded, back and forth, between home-fragments with me - who had made it through with me, and this meant that perhaps, I had made it through as well.

And in time, I stopped telling this story, stopped thinking about it and stopped trying to make sense of what happened - and went on to focus my by now very long-term psychotherapy on my own initiation into the profession. It was a senseless story anyway. My family was senselessly targeted, by a senselessly sociopathic clergyman, who committed senseless acts that could never be understood or contextualized. As long as my parents lived - they were full of sins of commission, distortions, self-justifications and avoidance. They never spoke of it, and to ask out loud, or even to wonder in private felt like an act of insurgence.

I eventually let the story go having done all I could to neutralize its power in my life.

I assumed, like many other mind-boggling stories of immoral behavior that I hoped to neutralize over the course of my career that the story had become a static, frozen. That the charge had been drained and it had come to rest.

But then my mother died.

And the weeks that followed, after sleeping off the exhaustion of a two years of care-taking, the old story had become dislodged, had shaken loose and re-animated itself.

I was suddenly possessed by questions my mother would never have tolerated or permitted, that would have enraged and shamed her or both. Questions that would have threatened her very core. She had manufactured her own story to live in, a myth that she was a ferocious protector, a heroic Mama Lion, recasting humiliations and debasements as acts of courage and daring.

And I realized I knew nothing. I had no facts, no data, no history, no context. I didn’t know the story of my own family, or what happened to us, or why we had been subjected to it.

I’d sit to mediate, or write or reflect and these questions - realizations - asserted themselves intrusively:

“How old was he? He seemed ancient…”

“What was that weird bible study group?”

“Didn’t he write books or something?”

“The Korean War? Or World War Two? Did he say he was a medic?”

“When did he and Mom get married?”

“Didn’t he have like ten siblings or something?”

“Wasn’t one of them named Margaret like Mom?”

“There must be church records about all of this somewhere, right?”

“When did he become a priest anyway?”

“Playboy? Did he tell once tell us he had stories published in Playboy?

Nagging questions rose up, and I would entertain them briefly before pressing them back under. They would have refused to answer but now there was no one to ask. They were all dead and gone. And I’d push the questions back down.

I’d already made as much sense of it as I could on my own. Whatever remained unsatisfied, incomplete was going to stay that way. No point in digging up old bones. It was done. Processed. I had extinguished the chilling story of my step-father-priest, and I had exorcised its influence on me as much as anyone could.

Of course, no trauma is ever fully processed, it surely left its mark and lived in my body as all trauma does - chronic migraine, various low grade autoimmune problems - my body retained the hyper-vigilance, the over-reactive adrenal responses to stress and challenge. And eventually it would turn out - a unique unheard-of cancer in my very core, lodged up and down my spine, floating through my cerebral spinal fluid.

I had used my anxieties like rocket fuel to organize a household, care for my elders and children, run a psychotherapy practice, administer a non-profit organization. I knew how trauma lived in my body, I knew how to use its side effects, and how to tend to its intractable symptoms. I knew how to make use of its reactivation as a therapeutic tool and use it to help others surviving their own trauma and crisis.

I’d literally made a career out of this stuff. I fed my family off my well processed trauma.

There is a space where the therapist’s history and lived experience becomes the seat of empathy, stitching together the client’s life and the therapist’s life through an intuitive experience of association and identification.

All psychotherapy is memoir. Any therapist worth their salt meets their client’s souls at the site of their own wound. The psychotherapist story is always present, always activated, always seeking entry points, portals from our own life stories that will serve to launch us into our client’s world. Allowing us to look down to see our own feet inhabiting our client’s shoes.

We can only start with our own pain, our own brokenness to meet the broken spaces in the other. To avoid doing so is akin to approaching a naked, bleeding man wearing a full suit of armor, weapons drawn.

Therapists seek out commonalities with our clients both consciously and unconsciously. The point where we become aware of the collective myth - the way we all succumb to the dominant narrative - and the way we might support each other in resisting - and make space for our unique and specific narrative burdens.

To acknowledge my client’s narrative burden, their lonely individuality, I must also be able to name my own - to claim the spaces where I am not normal, to reject the stigmatization of hiding, of passing. There are dangers of being subsumed by conformity, and there are also abuses and oppressions that can only emerge when we are able to pretend that our private, individual narratives are “normal” when they are not.

Psychotherapy, in its most sacred form, is about supporting, healing and celebrating our abnormalities, not eradicating them. It is about the audacity of flying your freak flag, and the loneliness of acknowledging all the way our lives have alienated us from the “normal” story.

What happens to a hero who encounters dark forces he cannot defeat? Where do we turn when we have angered the gods or fate has turned against us? How do we restore ourselves to wholeness when we have committed a sinful or destructive act? What are the benefits, challenges, and processes of forgiveness? What happens when we are overcome by greed, by starvation, when we are seduced by the impulse to power and dominance, status or reputation? What is hubris? What is evil? What are the dangers of zealousness? Of self-righteousness?

These are ancient questions - asked and answered and asked again by every culture, religion, generation, civilization, and tribe. These were portals of identification that I accessed when I sat with clients who were wrestling with sacred, eternal, existential questions, just as I had.

As so many must.

August 2015, New Jersey

I dream again of Father. A tangled dirty root ball, an entangled mass of good and evil. Planted in the ground like a perennial to emerge in a later season. It takes a long long time to see what good can grow out of evil. Then I dream of Lot's wife and never looking back. How many worlds and environments and people I shed as I fled the catastrophe. And how I kept fleeing until I was on solid ground.

I wonder if it is still dangerous to look back.

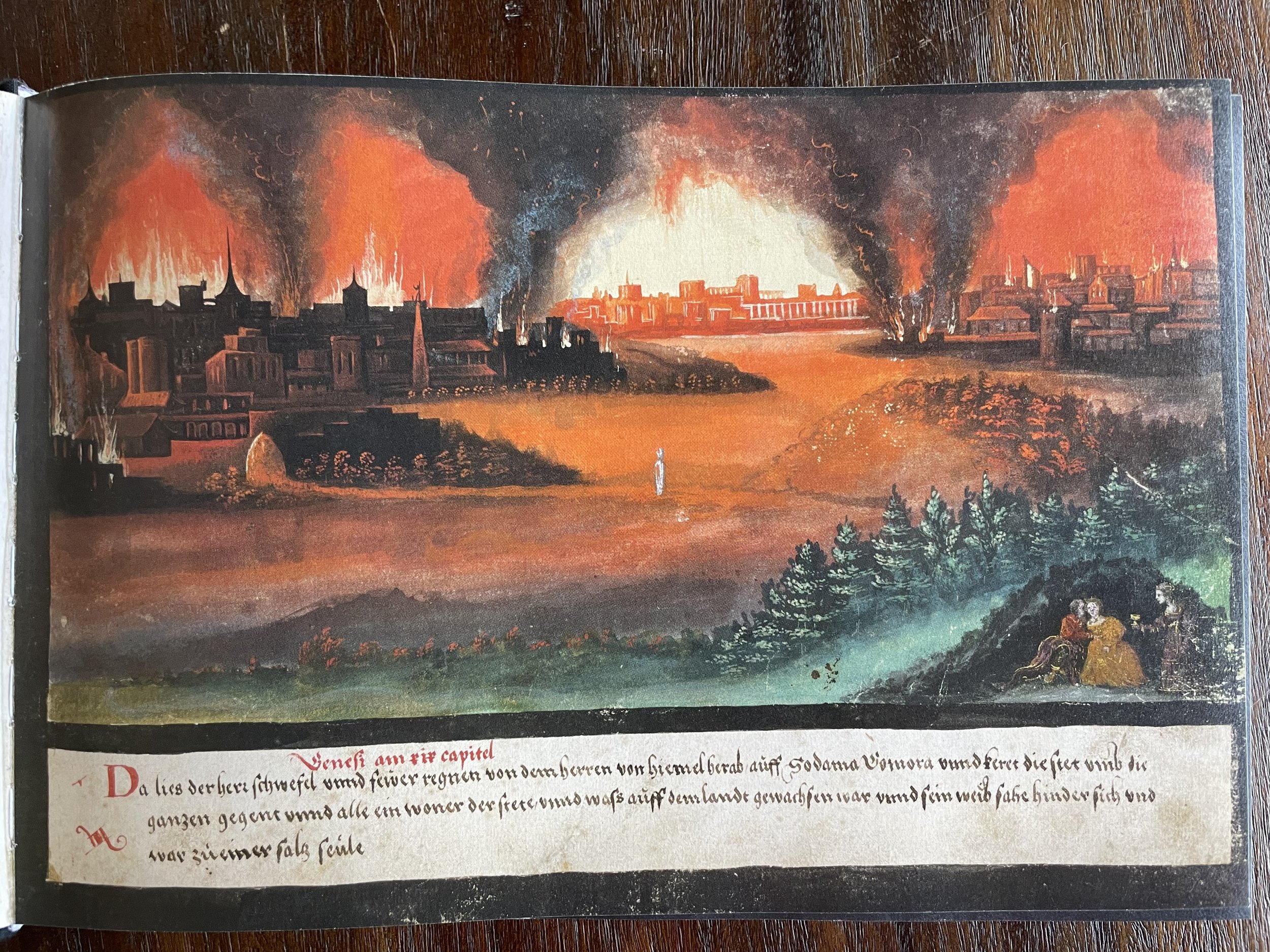

I climbed up to our third-floor study, carrying a heavy box. A Book of Miracles, a collection of illustrations from the German renaissance, depicting visions and miracles of the era, and the Bible which had just arrived in the mail. I cracked the book open and was gripped by a terrifying painting of the devastation of Sodom and Gomorrah. The Lord’s punishing wrath - a flaming holocaust. The city depicted as a giant pyre, on a near nuclear scale. And in front to it one small white column, a centimeter high, , standing alone, a tiny salt pillar in a field of embers and towering flames.

Abram had negotiated with the Lord to try to spare the cities: arguing that the smallest presence of goodness, should be enough to redeem the overwhelming evil.

“Will you indeed sweep away the righteous with the wicked? Suppose there are fifty righteous within the city; will you then sweep away with place and not forgive it for the fifty righteous who are in it?” ~ Genesis 18:22[i]

But when he searches, he cannot find fifty, so Abram eventually haggles the Lord down to ten. Ten good men in a city of hundreds of thousands of evil men should be enough to redeem and forgive them all.

But there were not even ten.

Sometime the presence of goodness is incidental, and not redemptive.

“When morning dawned, the angels urged Lot, saying “Get up, take your wife and your two daughter who are here, or else you will be consumed in the punishment of the city. When they had brought them outside, they said, “flee for your life; do not look back or stop anywhere in the Plain; flee to the hills, or else you will be consumed” Genesis 19:15-17[ii]

This is not only a story of looking back, but the story of what can happen when you look back.

“But Lot’s wife, behind him, looked back, and she became a pillar of salt.” Genesis 19:25[iii]

I’d thought the story of Lot’s wife was a story about disobedience and punishment. God’s punishment for breaking an arbitrary command: “Don’t look back.” Of course she would want to look back, she would need to look back. It was her home.

But looking at this painting - I saw, for the first time, that it wasn’t punishment.

It was a prescription.

It was a prescription to protect her from being engulfed again by trauma, to spare her from becoming lost to a post-traumatic paralysis. The angels of the Lord told her if she looked back, she would become paralyzed, frozen, like a pillar of salt. Don’t look back while you are in proximity to danger. Don’t look back while it still burns, while the rings of trauma still spread across the land - run to safety. You must travel a great distance before you can begin to contemplate what has been lost.

Jehovah’s angels warn us to never attach our identities to a trauma, to the stimulation embedded in trauma. They caution against getting stuck in traumatic bond to traumatizing people, places, events.

Is the opposite coast enough distance? Is forty or fifty years enough time? Is it still too soon when the central characters in the story are dead?

“Will you indeed sweep away the righteous with the wicked?” Genesis 18: 23[iv]

The wrath of Jehovah rose up within me. I yearned to burn it all down. This story is the story of bargaining: Should it all be destroyed? Would my world have been better off without any of it? Would I find fifty, ten, five, even one reason to forgive? Would there be there a single reason why I should not burn it all down, wipe it out of my consciousness, toss every memory on the smoldering heap, until there was only rubble, not a single stone left standing on top of another?

Would I find one upstanding citizen? Could I tell this story - could I look back - or would I be stunned into crystalized paralysis, an immobile pillar of salt?

I assumed that after forty years, and a good twenty in psychoanalysis, that enough time and distance had been traversed, and I would be safe from the aftermath. But just six weeks after the dream of a tangled ball of good and evil in the roots of a tree - a slow wave of excruciating pain, followed by a numb paralysis began creeping slowly upward through my body. It began at my toes, slid up the outside of my right foot, through my outer ankle, up the leg to my right hip and my right lower back. It became hard to walk. It turned out that a cluster of cancerous lesions had slowly chewed through the nerves at the bottom of my spinal cord.

Maybe it is never safe to look back.

1972 - Minnesota

The whole point of a pact with the Devil lies in the fact that is involves a relationship with a bad object. ~ Ronald Fairbairn[v]

We’d started going to Trinity Episcopal Church since I was in second grade, in 1972. (It was easy to calculate when things happened in my childhood because I started first grade in 1971, second grade in 1972, etc.) Before that we hadn’t gone to church really. Maybe once. For Easter with my Dad’s mom, Grandma Alice. But then my parents heard that there was a dynamic new reverend over at Trinity. People were talking - young families, were starting to attend - he was revitalizing the community they said.

I opened the office door one Sunday before services - and walked up to the freckled frowning secretary. She wore cats-eyeglasses which even my grandma didn’t wear any more they were so old fashioned. You can tell she curled her wispy red hair with the kind of bristly rollers that you sleep in. She ran her finger underneath her small-faced Timex watch on a stretchy metal band which seemed to dig and pinch into her chubby wrist. She wore a beige dress with a faint print that matched her freckles. She was almost invisible, camouflaged, against the light brown speckled wall to wall carpet and the pale grey file cabinets behind her metal desk.

All the kids knew she was mean. Father had a bowl of special toffees in his office for kids after church - and she never let us go in and get one if Father wasn’t in there - even if you’d asked Father and he’d given you special permission and told you to tell her so.

But this day I was not there for toffee.

“No, you can’t have a candy now. It doesn’t matter if he said you could or not.”

She is Father’s wife, and she is the boss of him I guessed.

“I want to make an appointment.”

“An appointment?”

“To talk about somethings.”

“Oh, well then. He could see you next Sunday at one o’clock after people start leaving.”

“Okay. My name is Martha.”

She knew my name. But I’d always found her scary and tried never to talk to her by myself. Father came over to our house a lot, but he didn’t bring her.

“All right Martha. He will see you next week at one.”

No toffee this time.

The next week he offered me a seat and told me I could take two pieces from the candy bowl. I had some questions:

“Well, I’ve been thinking about this a lot, and I keep wondering about it: If God loves everyone, does God love the Devil? So, are we supposed to love the Devil too? Will God and the Devil become friends again someday, will God forgive him or what? I thought maybe I should I pray for the Devil to become good again, but Mom said I should ask you first. I feel bad for the Devil.”

He tilted his head and looked hard at me before answering.

“These are certainly questions that are too big for you to have to carry on your shoulders. I think God can take care of these problems all by Himself without your having to concern yourself. Such big problems are for God to take care of on His own.

“I just always think about it when I say my prayers, or when I read the Bible, and the story of the serpent in the Garden - God must have let the serpent be there, you know, put the snake there. Or when we learned about how God and Satan talk to each other like with Job. Jesus never seems too mean to the demons - they all call out his name and they all know him right away - and he just always tells them to stop making trouble. Do you think Jesus feels sorry for the ones who asked to go into the pigs? I can’t tell? If God doesn’t hate anyone that means he doesn’t hate the Devil either, right?”

“I think that one day God probably will forgive the Devil. But that is a long long time from now, and that is for God to worry about. Not. You.” he said, booping my nose with his finger.

“Your parents are probably waiting, why don’t you take another for the road?” he said as he pushed the toffee bowl closer. “I’ll be by after services this afternoon. I’ll bring you a book you might like.”

I wandered off to find my parents, relieved, if only for the time being, with an extra chewy candy in my pocket.

I would go kneel at the communion rail to receive a blessing from Father knowing that we had a special, secret, attachment. He knew me, my family. He was my Dad’s best friend. He was at my house all the time. He was part of my home.

That night after church he came to the house with a gift. A book and a record album. The record was of the author reading most of the stories and essays in the book out loud. Some parts of the book, Father said, might be a little grown up for me, but he said it talked about some of the same questions that I worried about, but in a different way - and that if a part was too hard to understand, I could listen to the record and maybe that would help it make more sense to me. The book was called The Way of the Wolf, written by a priest named Martin Bell.

I thanked him and ran straight to my room with the book, while Father sat with Mom and Dad and Beth and listened to the first story on the record in the family room and drank wine. The first story wasn’t hard, it was written for little kids, and I was in second grade reading at an 11th grade level my teachers said. It was hard to find books that weren’t about grownups doing boring things, or baby books that were too easy. My favorite books were C. S. Lewis’ Perelandra and Narnia books, all the Oz books by L. Frank Baum, any of Madeline L’Engle’s books, and an illustrated Living Bible with pictures of a groovy white hippie Jesus. I’d read them all repeatedly and thought of them all as scriptures. This story from the book Father brought was just a kid’s story about a bunny, who sees a great silver wolf, sort of scary and kind at the same time - like Aslan in the Narnia books - that no other animals in the forest can see. And the bunny dies in a blizzard on Christmas Eve while protecting some baby field mice who got lost in the snow. He kept them warm with his body - and everyone was so happy the babies were saved, they forgot about the bunny. Except for the silver wolf, who comes and stands by the bunny’s frozen body.

It didn’t seem like a hard book to me: Barrington Bunny was supposed to be like Jesus who died for other people. And the wolf was God the Father I guessed. And the animals who made fun of Barrington and left his body in the snow were like people who had forgotten God’s sacrifice. I thought it seemed kind of stupid and didn’t have anything to do with the questions I was thinking about. I had been excited for a hard, interested grown-up book. I guessed the rest of the stories were children’s stories just as disappointing and that Father had underestimated me like most grown-ups, I supposed. I went back downstairs; I would thank Father again - and pretend that it was interesting.

When I walked into the family room - the bunny story was just finishing on the record player. Father was already standing near the stereo getting ready to lift the needle. I heard Martin Bell’s voice, trying to sound a little spooky and sad reading the last words of the story:

But the wolf did come.

And he stood there.

Without moving or saying a word.

All Christmas Day.

Until it was night.

And then he disappeared into the forest[vi].

Beth and Mom and Father were drinking wine, and Beth and mom were crying. Beth was crying openly wiping at her eyes carefully with a tissue trying not to ruin her false eyelashes. Mom’s eyes were all wet and her nose was red, but she was pretending she wasn’t crying. This all seemed ridiculous and disturbing to me. The Christ story was so much more upsetting and terrifying and heart breaking than this dumb bunny parable. We heard that every week in church. That story was vast and mysterious and strange and confusing and excruciating. But this silly story had somehow made them cry? I teased my mom:

“Are you really crying Mom? About a bunny?”

“Oh, stop” she said wiping her face with her arm.

I could see that Father was pleased it had worked on them.

“I thought you might like the next one Martha.”

It wasn’t a story. It was Martin Bell talking about lots of different things that somehow all still fit together. He talked about the chosen-ness and the brokenness of the people of Israel:

Enslaved by the Egyptians.

Crushed by the Assyrians

Broken by the Babylonians

Desecrated by the Greeks

Tyrannized by the Romans

Exterminated by the Germans

The chosen people of God.

The elect. [vii]

The last are first. The first are last.

Next Martin Bell talked about a baby born on a downtown sidewalk, while a mother screamed for help, while no one responded, and an unnoticed star appeared in the sky over Oklahoma City.

He told a joke about an astronaut that sees the face of god - It was a joke I’d heard my Dad tell other white men before when my mom wasn’t in earshot - and the astronaut comes back to earth and everyone asks what God looks like, and the astronaut said:

“God? Well, she’s Black!”

But the way Martin Bell told it, it was no joke, and I could hear that the way my dad and other men told it was sinful. God was absolutely present in the face of a Black woman, maybe even especially. God was present wherever there is suffering, wherever there is oppression. God always comes to the persecuted first.

My mother and Beth began to gather up plates and carry them off to the kitchen, while my Dad, looking a little annoyed, stubbed out a cigarette in the ashtray. I saw Father give a small knowing nod and I took note of his pleasure at Dad’s discomfort. He’d played this on purpose.

As for me, there was something about this story, or was it a sermon, that made my heart pound and the sky open wide and the universe turn itself upside down:

And then God manifested himself– revealed himself

As an outlaw.

A fugitive from justice.

He was masked.

No one.

No one!

Knew who he was.[viii]

My dad stood up slowly with hands on the coffee table to protect his damaged back and waddled his duck-footed-bad-back walk off to the kitchen to grab another Coca-Cola. Father and I sat and listened. He sat sideways on the orange couch, his arm draped around the back. I sat across the room on a big floor pillow, with my back against the built-in stereo speaker. I could feel Martin Bell’s voice vibrating up and down my spine.

And these are the signs by which you will recognize him…

He will not look like God.

He will be masked.

There will be no room for him in the world. [ix]

“You like it? Do you see…” Father whispered to me during a pause.

I nodded, listening intently, not wanting to miss a word:

Only very wise men and children will ever recognize him.

And he is here today. Because

You

Are the Christ.

The chosen one.

The broken one.

The one who is ripped apart and torn into

shreds

and scattered

and dispersed

and despised

and chained….[x]

This made more sense to me than anything I had ever heard or read about God, than anything I had heard in Sunday school. I didn’t know why it made sense to me, but it did. This was the only way I could understand the impossible questions that the Bible activated in me, the feelings that came with the sound of this man’s voice on the record, reading these strange and haunting words. Father smiled and nodded. “I thought this might be just the right book for you” he said.

This is your mask.

Surprised? You should be.

Unbelieving? Naturally.

Frightened? I should hope so. [xi]

I was frightened, as I should be.

Later in my room, I read all the mysterious haunting chapters that had been hidden behind the Barrington Bunny essay, like they were a secret gift just for me. These words felt like they unlocked something in the center of my brain, something old and something I had always known but couldn’t find words to explain to anyone - but it had to do with a picture of God that wasn’t only “love” - unless “love” meant something wilder and more primal and elemental than what most people seemed to mean when they said it. It was about trying to conceive of a God who became impossible, a god with so many faces that all cancelled themselves out and contradicted each other, whose love was terrifying and liberating, and violent and relieving all at once.

This was better than an answer to my question. This was an introduction to someone who was wrestling with the same questions I was, and proof that I was not the only one who did not hope for a God who would make life any easier.

There was a story of a boy, named Thajir, who the wind chose especially, to whisper all its secrets to, that no adults would ever hear:

Regardless of what anyone else may ever tell you, regardless even of what your own experience may lead you to believe, you are everyone who ever was and everyone who ever will be… Anything that hurts anyone, hurts you. Anything that helps anyone, helps you. It is not possible to gain from another’s loss or to lose from another’s gain. Your life is immensely important. Thajir do you understand this, or is it too difficult?[xii]

I understood. It was not too difficult.

There were other stories that were written for grown-ups, and I understood them too. Stories about doing what is right for other people, no matter what it cost, no matter if it killed you. Stories about how following God can tear your life to pieces. A story about how Jesus cured ten lepers, and only one returned to thank him, and how it is too easy it is to blame the ones who did not:

That condemnation is easier than investigation– that if we take time to investigate the reason why people act as they do, we would find that they have to act the way they do, and that such action in the light of circumstances is quite understandable and totally forgivable and even completely reasonable and just as it should be?

You already knew that. [xiii]

I did.

There was a story about Easter that started like this:

Something like an eternity ago, human beings got all caught up in the illusion that being human is a relatively unimportant proposition… What is more tragic, of course, is that in the wake of that basic error there quickly followed the idea that human beings are expendable, which easily degenerated into the idea that some human beings are expendable. Certain human beings are expendable. Really bad guys are expendable. Guys with low I.Q.’S are expendable. Anyone who disagrees with me is expendable. [xiv]

These were the kinds of arguments that spun around in my head at night, that churned in my head when I went to church or read the Bible. These were the kinds of resolutions I would come to, stories out of my own bones, that I would have to find by myself in bed at night, before I could reach the peaceful place in my brain and drift off to sleep.

This was why I had made an appointment with Father in his office.

These were the questions he said at first, I shouldn’t have to worry about, but he could see I did worry about anyway. If God was in us all, wasn’t Devil was in everyone too? Wasn’t every person I met also the wind and the bunny, and the boy called Thajir and the wolf and the animals and the grown-ups that made racist jokes and the astronaut and the parents that didn’t believe, and the lepers that forgot and the one that remembered?

These questions were so different from the ones we were asked and answered at school. These questions were alive, like living words. Answers that stepped for a moment into plain sight and then disappeared if you looked away for a split second.

The book cover said that the man who wrote this book was a minister and a Pinkerton detective. At the same time? How could you be both? How could you be a man that looked at scary and dangerous things, that carried a gun and be a priest?

Maybe it was like the “secret book” that Father had written under a “secret name.” Maybe Father had a second secret life too.

One afternoon when my Mom took my brothers to the doctor’s office (they were always going to the doctor’s office with severe asthma and allergies), Father said he could stay with me for an hour or so and brought another a record for me to listen to. It was Jesus Christ Superstar- which I had heard some of before on the radio and at my friend Katie’s house. Father and I listened, and he explained which characters were singing so I could follow the story.

“This is Judas before turning Jesus in – and listen now - he says he doesn’t even want the silver - he just thinks Jesus is making dangerous political decisions - And Jesus tells Judas ‘do what you have to do’ and we see that Judas doesn’t even have a choice - it is the part in the story that he is destined to play.

“And listen to the music - Jesus isn’t mad at him, it sounds like he forgives him before Judas even understands what he has done… And here, listen this – this is when Judas hangs himself in remorse - He is destroyed, horrified to find out what they have done to Jesus, what he has done…. Hear how this chord sounds like a scream? It is as if Judas was a sacrifice too. Hanging from a different tree at the same time. One is damned for all time. The other is the Savior.”

A long time ago, human beings got all caught up in the illusion stoa being human is a relatively unimportant sort of proposition.

Well, that’s not true. It’s wrong. All wrong. From the creation of the heavens and the earth, it has been – wrong. There is nothing more important than being human. Our lives have eternal significance. And no one – absolutely no one – is expendable.

And these were the worries I had whenever people talked about hell or descending into hell. And I understood as we listened that Father had such questions stuffed inside his head too and not too many people who wondered about them with him. I understood that giving me books and sharing these stories with all these flickering appearing and disappearing answers in them was relieving for him too.

These were lessons that penetrated my psyche before I had defenses, before I could think critically, before adults were fallible.

And I also know that these secret thoughts lived hidden away in my head independently of Father Clark, before him, but he was the only one who knew about them and helped them grow. Numinous truths. Non-dual truths Tangled-up truths. These thoughts buzzed and wrestled with each other in my head and in my chest until they transformed into relief. A rock to stand upon. These buzzing, living paradoxical thoughts that had taken up residence like seeds inside of me, would transform into the strange solid faith that I would rely on to survive the man who nurtured them and helped them take root.

Don’t be afraid. I am bringing you glad tidings of great joy.

For out of you this day the Christ is born.

God loves you.

Amen.

Don’t be afraid.

Amen.

It is good to be as broken as you are.

Amen.

Be nice to each other.

Amen.

It’s good to be you.

Amen. [xv]

I would whisper these words to myself whenever I was afraid.